“Like no other sculpture in the history of art, the dead engine and dead airframe come to life at the touch of a human hand, and join their life with the pilot's own.”

― Richard Bach

The next morning, we were at Pease before the sun rose. I was ready to get going. It seemed like it had been an eternity since we were in the air heading home. I thought we'd be there by now, the journey long over. But here we were, still in spitting distance of the Atlantic Ocean, granted at least on the right side of it, the worst (in my mind) of the trip, the ocean crossings, over, but still, we had thousands of miles to fly to get home.

The leg we planned to complete today, Pease to Chippewa Valley Regional in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, was 900 nautical miles (1,030-plus statute miles), a very long haul, but I was ready to roll and get it over with. We still wouldn't be home once we got there, not by a long shot -- or flight. We'd still have to cover another thousand miles to touch earth at the old homestead. America is big.The morning was already warm, portending another hot, humid August day. We pulled the props through. No hydraulic lock. Pre-flight inspection: all okay. I opened the cabin door at the rear and clambered aboard, happy to see the now-familiar interior once again, smell that unique old airplane aroma. What is it made of? I don't know. But I recognize and like it. I stowed my gear securely, mostly my traveling clothes and the souvenirs I'd picked up for the folks back at the ranch. I'd done some grocery shopping the previous evening and had the fixings for sandwiches for us -- Kaiser rolls, Semelle rolls, sliced roast beef, sliced ham, thin-sliced dry toscano salami and pepperoni, hard-boiled eggs, greenleaf, coral and iceberg lettuce, cucumbers, sweet red peppers, bean sprouts, avocados and tomatoes that I'd prepared for sandwiches and stored in containers, mustard, horse radish, mayonnaise and butter packets, thin-sliced Swiss, Cheddar and Provolone cheese, seedless grapes, sectioned apples and pears, Saltine and Ritz crackers, potato sticks and chips, Fig Newtons, sparkling water.... I probably overdid it, bringing aboard enough food to feed a small army. I stowed all this forward behind the cockpit. I was not tense and keyed up as I had been during the Atlantic crossing and Canadian legs of the trip and looked forward to noshing away the hours watching the landscape roll by under our wings, each minute taking us almost four miles closer to home.

I settled into the left seat, saying under my breath, "Hello airplane," and patted the steering column. I looked over the controls and gauges to re-familiarize myself with them, reaching out, locating and touching switches and levers, naming them in my mind and recalling how they worked -- throttles, mixture levers, manifold heat levers, cowl flap handles, ignition switches, engine selector switch, starter switch, primer switch, ignition booster switch, propeller levers, propeller feathering buttons, propeller anti-icing knob, de-icer button, pitot heat switches, windshield wiper switch, oil shutter levers, oil bypass buttons, oil dilution switches, engine fuel selector handles, suction cross-feed handle, fuel booster pump switches, engine fire extinguisher controls, master switch bar, battery switches, generator switches, voltmeter switch, turn-and-bank power selector switch, instrument inverter switch, aileron trim tab wheel, rudder trim tab crank, elevator trim tab wheel, wing flap lever, emergency hand crank for same, landing gear lever, landing gear emergency clutch, landing gear lever emergency release, tail wheel lock control, parking brake handle....“When he climbed into the airplane, the same transformation always came over him. He exchanged his earthly freedom of thinking for what had to be a series of disciplined facts. To absorb and segregate these facts, all in their right and proper order, was his duty. Not only was it his duty but it was his sole defense against depending on luck; and although he was aware of the power of luck, he never considered trusting it when he was flying.”

― Ernest K. Gann

Dad settled into the right seat and got busy with the radios while I fiddled with the GPS. Then we both went over the flight plan one more time and went through the pre-flight check list: this and that off, off, on, off, on, on.... It was already hot in the cockpit so I opened my window and dad did the same to his. The air was still and no breeze entered.

“As the years go by, he returns to this invisible world for peace and solace. There he finds a profound enchantment, although he can seldom describe it. Flying is hypnotic and all pilots are willing victims to the spell. Their world is like a magic island in which the factors of life and death assume their proper values. Thinking becomes clear because there are no earthly foibles or embellishments to confuse it. Professional pilots are, of necessity, uncomplicated, simple men. Their thinking must remain straightforward, or they die—violently.”

― Ernest K. Gann

We'd kicked the tires, metaphorically speaking, and now it was time to light the fires and turn gasoline into noise. Left engine fuel selector handle: left front; left cowl flap handle: open; left throttle: ease to one-eighth open; left mixture lever: full rich; left fuel booster switch: on; master ignition switch: on; engine selector switch: left; starter switch: on. The propeller starts to turn, count the blades revolving past the window: one, two, three, four. Then left ignition switch: both; ignition booster switch: on; primer switch: on. The top five cylinders cough and bark into life, followed, always reluctantly, it seems to me, by the lower four. Once the engine is running smoothly, release the primer switch, release the starter switch, release the booster switch, adjust idle speed, fuel booster switch: off, engine selector switch: off. Then do the same for the right engine. Once it's running smoothly, instrument inverter: on. Recheck the radios. When the oil temperature is within range, re-adjust engine idle, move propeller control levers to take-off rpm to get the maximum amount of air blowing over the cylinders to ensure the engines don't overheat.

Now we taxi into the wind, brake to a stop, lock the tail wheel and set the parking brake, set engine idle speed to 1500 rpm, push in the left propeller feathering button. The rpm should drop to 450 rpm. Once it does, proving the feathering system is working, push in the feathering button again to unfeather the propeller and hold it till the engine speed comes up to 1000 rpm, then release it. Do the same for the right propeller.

| |

| Pilot thought fuel switch was on main tank. It wasn't. Both engines quit after take-off. |

That done, lower the flaps to 25 degrees while watching the volt and load meters as the flap motor operates, making sure the the voltage does not exceed 29 and the draw no more than a 0.3 load. And check to make sure the flaps really are at 25 degrees. Then pull the right propeller lever to the low rpm/high pitch position and make sure the engine speed stabilizes at 1150 rpm. Once it does, push the propeller lever back to take-off rpm and make sure the engine rpm rises to 1900 rpm.

.jpg) |

| What happens when you don't follow procedure to the letter. |

However, I won't bore you with all this dull piloty stuff. Some pilots get bored with it, too, and get careless, assume everything is in working order and positioned or set as it should be and don't verify that it is. But they don't remain pilots, or on this Earth, for long.

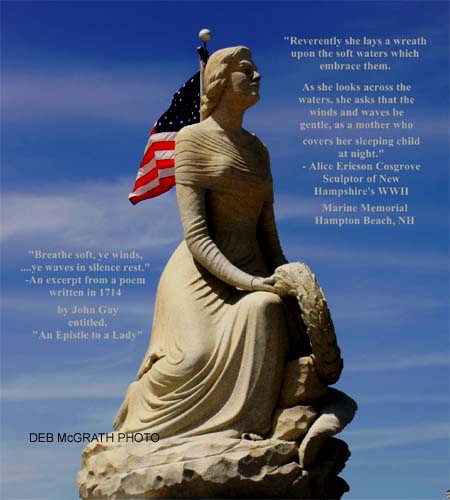

By and by, we do leave mother earth, climbing southeast over the coast, saying good-bye to Portsmouth on our left and Hampton on our right, circling north over the ocean, passing by the Isles of Shoals, covering distance in minutes that took more than an hour on the sailboat, finally settling on our destination heading, West by north, cruising altitude 10,000 feet and airspeed 186 knots, fuel burn with our brand-new carburetors and tuned engines 42gph. That gives us a good six hours of flying time with a 45 minute reserve, allowing us a calculated range of over 1100 nautical miles, so Eau Claire is easily in range and we'd reach it with our usual five hours or so flying time that we'd done on each leg of this trip (excluding BTV to PSM).

We had left the hotel too early to have breakfast so once we were settled in for the long haul I let dad take the wheel and I went back to the cabin and fixed us sandwiches and coffee. Dad wanted ham and Swiss with mustard, garnished with green leaf lettuce on a Kaiser roll. He also wanted a boiled egg and some chips on the side. I made the sandwich, peeled the egg, put everything in small cardboard container along with some napkins and a Handi Wipe and handed it up to him along with a fresh cup of coffee and a pint-size bottle of sparkling water. I made myself a tomato, coral lettuce and Provolone sandwich with mayonnaise on a Semelle roll with some potato sticks on the side.

We put the Beech on autopilot while we ate, not saying much, just enjoying our meal and the view. I was hungry enough that I was tempted to make myself a second sandwich, but instead I ate slowly and when dad couldn't finish his chips I scored them. After we were finished, I took everything back into the cabin and cleaned up. While I was doing this, dad let loose a loud, long belch. I guess he enjoyed his meal.I called out, "Did I hear a barge coming through?"

"Don't get smart, young lady!"

"Too late!"

I poured us each a cup of fresh coffee, black as we both liked it, and settled into my seat in the cockpit. I wondered if we should not start using oxygen at this altitude but dad, after asking me if I was feeling okay (I was), said he didn't think it was necessary. We'd both hiked and climbed mountains higher than this with no ill effects, but if we needed to climb higher we should break it out. We had an SpO2 meter and I fished it out and we both checked our status: A-OK. We decided to do that every half hour. Why were we flying this high today? Winds aloft forecast made this the best altitude choice to avoid headwinds. In fact, we had a nice tailwind and our ground speed according to the GPS was a good 220 knots. I hoped it would last but knew it probably wouldn't.

Below us, the morning sun casts long shadows over the earth, every undulation of the land, every structure, every tree declaring itself with a dark doppelganger. I could see mountains ahead and thought that if I had all the time in the world I would like to explore them as I'd never been to this part of the country before. Upstate New York, as well as New England, were storied parts of the founding of our country about which I was only familiar through reading -- Arundel, Drums Along the Mohawk, The Musket and the Cross, In the Hands of the Senecas, to name four by Walter D. Edmonds that stick in my memory. I recalled being struck by Edmonds' observation that the English overcame the wilderness while the French lived with it. At the time, I thought the French way was better, but reflecting now, I suppose that was a romantic view that in practical reality I would not have been happy to actually live. And, of course, Americans took that English attitude and ran with it, subduing the entire continent in a handful of generations. |

| Avis & Effie Hotchkiss |

|

| Adeline & Augusta Van Buren |

I remembered reading about two women, Adeline and Augusta Van Buren, who rode motorcycles across the country from Brooklyn to Los Angeles in 1916 in perfect safety. On their way, they rode their motorcycles to the top of Pike's Peak. A year before, a mother and daughter, Avis and Effie Hotchkiss, ages 26 and 56, had done a similar thing, but going from Brooklyn to San Francisco in a side-car rig, averaging 150 miles a day. Just a century earlier, only a handful of brave men, risking their lives against grave dangers, had crossed the continent -- and they walked or poled boats up rivers the whole way and only dared do so armed and prepared to fight and eating only what they hunted. The women slept in hotels and boarding houses and ate at restaurants. Their greatest danger was being arrested by local cops who thought women wearing pants was scandalous.

|

| An old, abandoned wagon-haul road. |

Looking down on all the green below, I began to think about the so-called greenhouse effect and global warming or, as it is now called, climate change. I could never figure why those that switched terms thought "climate change" was the more suitable phrase, as if the climate has remained unchanged for the last 4.5 billion years. I mean, really? But then I know well-educated, professionally accomplished persons who have never heard of the ice ages, don't know what or when the climactic optimum was, believe the climate during the voyages of the Vikings to Greenland and points west was the same as that of today -- assuming they know the Vikings did that. I don't mean to belittle them by saying this. Doubtless, there are any number of important things that I am completely unaware of, too. But it does show how difficult it is for a lay person to avoid being mislead about a particular scientific field.

For example, regarding atmospheric carbon dioxide, there has long been a scientific debate that doesn't include human activity about which is more important for its injection into and removal from the air. One side says the most important are abiotic processes -- volcanoes put carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, rain washes it out and it is then incorporated into calcium silicate rocks in an endless cycle, with sometimes more CO₂ in the air and sometimes less depending on random geological events. They note that as volcanic activity has subsided over the eons, there has been a gradual downward trend in atmospheric CO₂: the early earth's atmosphere may have been as much as 30 percent CO₂ and at the very least 5 percent, but by the beginning of the Industrial Revolution it had declined to a mere 0.028 percent. The White Cliffs of Dover are a prime example of carbon sequestration in calcium carbonate rock, burial grounds for the huge amount of CO₂ present in the air of the early earth and removed by geological processes.

Carbon-fixation from the air to life forms, from microbial mats floating in ancient coastal seas to continent-wide angiosperm forests, is what controls atmospheric CO₂ and has done so for billions of years. Angiosperm forests are particularly effective at removing CO₂ from the atmosphere, about four times more so than conifer forests, and seem to have led to a cooler earth since their evolution during the Cretaceous. Without angiosperm forests, it is believed, the earth would have been 20 degrees F. warmer than it was at the start of the Industrial Revolution.

Since life can't exist without carbon dioxide, it has been struggling to adapt to the constant decline of atmospheric CO₂. The efficiency of angiosperms in extracting CO₂ from the atmosphere has exacerbated this problem and resulted in the rise of the grasses, with vast areas of the earth that were once forest now prairie (or, more accurately, human-cultivated grasses -- wheat, corn, rice, etc.). Grasses began proliferating beginning about 10 million years ago during the Cenozoic, a period of intense glaciation that saw carbon dioxide drop to 0.018 percent of the atmosphere. Grasses expanded their range then and since because they are much better procurers of atmospheric CO₂ than angiosperms thanks to their significantly more efficient use of the enzyme ribulose diphosphate carbozylase (RuDPC). If a plant cannot send CO₂ in sufficient quantities to its RuDPC, it dies. Since atmospheric CO₂ is far below the optimum for vascular plants like angiosperms and other tree types, they have responded by using energy to mass produce RuDPC so that what CO₂ they can obtain from the atmosphere finds enough RuDPC to carry out the plant's metabolism. Grasses have evolved the ability to funnel CO₂ more precisely to their RuDPC and so need to expend less energy to produce it than do angiosperms or other vascular plants. They

don't need as much nutrients as trees do to survive and flourish, so they out-compete trees. Eventually, as the amount of CO₂ in the atmosphere drops even lower, trees will disappear from the earth and it will become a grass planet. But then, as atmospheric CO₂ declines yet further, even grasses won't be able to survive and the planet will become as dead as Mars. This will happen, scientist James Lovelock estimated, in about 100 million years, by which time man and all his works will long have vanished from the earth, and whatever rise in CO₂ in the air his activities produced will have dissipated, the only result a brief increase in limestone production.

don't need as much nutrients as trees do to survive and flourish, so they out-compete trees. Eventually, as the amount of CO₂ in the atmosphere drops even lower, trees will disappear from the earth and it will become a grass planet. But then, as atmospheric CO₂ declines yet further, even grasses won't be able to survive and the planet will become as dead as Mars. This will happen, scientist James Lovelock estimated, in about 100 million years, by which time man and all his works will long have vanished from the earth, and whatever rise in CO₂ in the air his activities produced will have dissipated, the only result a brief increase in limestone production.We expected to encounter some building thunderstorms over the Midwest, so when the bright sun at this attitude warmed the cockpit enough to make dad drowsy he clambered out of his seat telling me he'd take a catnap now to be fresh for the upcoming events and stretched out on the couch in the cabin. Alone in the cockpit, I wished we already had all that upgraded avionics gear he had talked about getting, especially weather radar and a Stormscope or Strike Finder and XM Weather. I did not like flying through storm fronts. I guess we'd be talking to ATC a lot, and if things got very sketchy, there were plenty of airports we could divert to. Looking ahead at the hazy horizon and clear sky, I hoped it would stay that way.

In about a half an hour dad was back in the cockpit with a fresh cup of coffee. He offered to make me one, too, but I was coffeed out. In fact, I felt drowsy myself, so, for the first time, I went back into the cabin and, wrapping myself in our wool blanket, stretched out and let myself relax. Resting my ear against the couch back, which was mounted against the side of the cabin lengthwise, replacing what would otherwise have been two seats, I could hear the susurrous slide of wind rushing past the fuselage. The steady drone of the engines was quieter back here than in the cockpit. Looking up, I could see sun shadows on the cabin ceiling. The rays streaming through the windows were filled with dust motes dancing in the light the same way they did in your house down on Mother Earth. I watched them until my eyes closed involuntarily and I was asleep.

A dream dissolved as I awoke. One moment I was deep in that alternate reality and then suddenly I was back aboard the Beech. More than an hour had passed. I hadn't realized I was that tired. I sat up, elbows on my knees, head in my hands, still groggy with sleep. The sun shadows and light beams had shifted aftward, the sun moving west ahead of us. I washed my face, cupping water in my hands and drying off with a paper towel, made a cup of coffee, asking dad if he wanted one, too (he didn't), climbed into the cockpit and buckled into my seat. We had descended several thousand feet, having run into a steady headwind. We still had one, though not as strong, so we were just about to drop down a few more thousand feet when I sat down. I was content to let dad do the flying while I just looked out the window and sipped my coffee. My mind felt fuzzy. I wanted to go back to sleep. I checked our position, noting how far we'd come, how far we yet had to go. We weren't as far along as I had hoped. I wished now that I had kept sleeping. I don't know why, but I just wanted this trip over with. The feeling was very strong for some reason. I wanted to see my kids, to see our living room with its stone fireplace and the view out towards the mountains, sit in the big farmhouse kitchen, bright with eastern- and western-facing windows, its cozy breakfast nook always piled with books, mail -- mostly bills -- account ledgers, shopping lists and everything but breakfast. I wanted to see my bedroom, my closet full of my things, my bathroom, my bed. I wanted to cook a meal for my family, made with choice, fresh ingredients, knowing just what would be liked by everyone. I never wanted to see a hotel bed or a restaurant meal ever again. I just wanted to be home.With me back in the left seat we dropped below 3,000 feet before we got out of the headwinds and began making good progress. We saw some thunderheads looming over the horizon to the south of us, but nothing close. That changed as we flew past Wausau, and a building storm front rose up ahead of us. We climbed to 10,000 feet to get over it, then climbed again to 16,000 feet, talking with ATC to get us steered around cells. We discussed alternates, even radically changing our destination, considered turning back to outrace the storm and get on the ground in clear air, but ATC said they could vector us through and the storm should have passed the airport by the time we got there. So we continued on.“Flying through thunderstorms, a pilot may earn his full pay for that year in less than two minutes. During those two minutes, he would gladly return the entire amount for the privilege of being elsewhere.”

― Ernest K. Gann

-1.jpg)

We hit solid clouds and some seriously bad turbulence as we neared Eau Claire, getting jounced around petty good. ATC was unable to vector us around the cells popping up, there were so many, and advised us to "navigate as required." I used the ADF tuned to an off frequency to try to avoid the the worst cells -- the ADF needle would swing in the direction of lightning discharges. That's where the most violent turbulence was. I'd turn away from those only to encounter more whichever way I pointed the airplane. Severe up- and down-drafts made holding our altitude a challenge. I reduced our airspeed to 130 knots, as slow as I dared go, to reduce stress on the airframe, and focused on maintaining the aircraft's attitude, nose and wings level, and let the weather have its way. We dropped so fast once that it felt like the big drop on a roller coaster, leaving my stomach playing catch-up. Then we were hurled upward just as fast. We got visible lightning flashes and once I thought I actually heard, or rather felt in my chest, a crack of thunder. The noise of the storm was terrific. Rain pelted us pretty good, sometimes in sudden, intense bursts that overwhelmed the windshield wipers, and hail rattled against the windshield and bounced off the fuselage and wings. It sounded like somebody firing bird shot against a metal garage door. I glanced out a few times to take it in, but mostly kept my eyes glued to the instruments. If I kept the needles on those gauges where they should be, all would be well. Dad could be my eyes looking out.

As I flew the approach to EAU, the wind was 130 degrees at 19 knots, gusting to 30 knots, visibility six miles in moderate to heavy rain, broken clouds at 8,000 feet, overcast at 6,000 feet, scattered clouds at 4,000 feet. I wanted to land on runway 14 but was directed to runway 4 so I came in like that famous Chinese ace, One Wing Low, maintaining my direction of flight with differential power, rudders and ailerons, creating a slip in line with the runway, adjusting the slip to counter the varying drift caused by the gusting crosswind. I had 8,100 feet of concrete to roll out on so I came in fast without flaps, as at Iceland, flying the plane onto the runway in the slip, straightening out just before touching down lightly on the right main, easing the left wing down till the wheel touched, holding the tail high as long as possible, working the rudders and doing some wrist action with the throttles to keep her straight. Then, as we slowed and the tail began to sink, I pulled the yoke back quickly but smoothly into my lap, dropping the tail wheel smartly to the pavement and holding it firmly on the runway. As the rudders lost effectiveness, I began tap-dancing with the brakes as well. Taxiing off the runway and to the ramp, which was not easy in that crosswind, the windshield wipers going like mad, the rain sounding like a freight train, we noticed hail on the ground. In some places it looked like snow, it was so thick. I couldn't believe it but I was cold. Really cold. I turned on the cockpit heating. Dad looked at me and nodded. The cold was not only from the weather, but from the heart. It had been pretty damn close there. I realized that I was repeating to myself, "Oh, thank you, sweet Jesus. Thank you!" Jesus may not have taken the wheel, but he put his hand on mine when I dearly needed it. You think that's silly? I don't care. I know what I know.

When I swung the tail around and set the parking brake, I let the engines idle, chugging at 450 rpm, just savoring the fact that we were on the ground, safe. It was very dark outside although it was still early afternoon. The rain, mixed with hail, was pouring down in sheets. I rested my hands in my lap. They were shaking. I couldn't stop the shaking. I lifted my right hand and pressed it to my cheek. It felt like ice. I tucked both hands into my armpits and shivered. Dad asked me if I was okay. I said, "No. But I will be. Just give me a minute." "You handled the airplane as good as anyone could have," he said. "And

that was a very good landing, little girl. I couldn't have done it better. No one could have." We looked at each other. Without speaking, what we exchanged was love, affection, understanding, comfort, relief.

To be continued...

.png)

%20and%20Star%20Island%20(left)%20%20Isles%20of%20Shoals.-1%20(2).jpg)

.jpg)

-1-1.jpg)

-1.png)

-1.jpg)